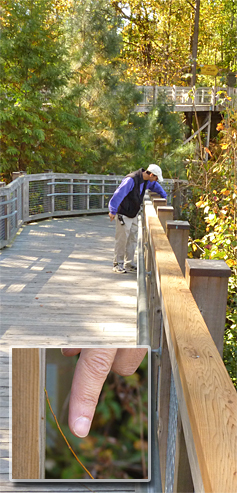

This is an ant. It’s about 3-4 mm in length. It’s walking along the handrail of the Museum’s boardwalk.

Where is the ant pictured above going? Where did it come from? And, what’s so incredible about it?

Warning: this is a long post, so if you don’t like ants, or reading, you may wish skip this post or just scroll through the images (but I think you should read it, it’s very interesting).

As I stood on the octagonal landing halfway down the boardwalk leading to the Wetlands, I noticed a slow, widely spaced stream of ants walking along the handrail. It was late October and the ants didn’t seem to mind the chilly temperatures as they moved across the rail.

I pass this location numerous times each day as I make my way around the trails of the outdoor exhibits. Each time that I walked down the boardwalk that day I checked to see if there were still ants moving along the rail. And indeed, each time that I did walk by, there were ants diligently working their way along the handrail. Most of the ants were marching along singly, many feet (or even yards) separating them from each other. Occasionally, they were in small “convoys.”

Some of the ants were going down the boardwalk, and some were going up the walkway. I also noticed that some of the ants moving up the boardwalk had somewhat swollen abdomens, and some carried small pieces of what appeared to be a white waxy substance in their mandibles.

False Honey Ants are subterranean nesting ants and are active during cold weather. Another name for them is Winter Ant. In fact, they are more active during the colder months than the warmer part of the year, staying out of sight for most of the summer.

I’ve seen these ants before, at sapsucker holes during mid-winter and other places where sap or nectar is flowing but, oddly, I never actually got around to finding out what they were.

The “false” part of our little honey ant’s name comes from the fact that there are Honeypot Ants, or Honey Ants, in the southwestern United States as well as other arid areas of the world, that store huge amounts of nectar, sap, or honeydew in their abdomens for later use by other members of their colony. Their abdomens may swell to the size of grapes. Our False Honey Ants do store sweet fluids within their abdomens, but certainly not to the extent of the true Honey Ants.

False Honey Ants send out scouts to locate sources of “honey” (honeydew, sap, nectar…), leaving a scent trail behind them so that they can find their way back to the colony, and more importantly, so that others in their colony can follow the trail to the source of their findings once the scouts get back to the colony and report what they’ve found. If you watch one of these streams of ants heading out to load up on goodies, you’ll see that they stick close to the trail laid down by the scout, even to the point of making little side trips off the main trail where the original scout may have temporarily wandered off the straight and narrow.

Sometimes, though, one of the ants may appear lost, as if it cannot find the trail, walking around in circles until it once again zeroes in on the scent. I watched several of our little adventurers do this as I studied the colony on the handrail. However, they always seem to relocate the main trail and continue on with their duties.

Where were these ants going and where did they come from? Well, with the able help of Ranger Lewis, we were able to narrow those two points down to near exactness, at least as far as where the ants had come from.

The ants began their journey down below the boardwalk, about 13 or 14 feet below the boardwalk. Their starting point was beneath the soil somewhere under the leaf litter near a rotting log.

The little ants walked across a root of a maple tree, onto and up the trunk, along one of the tree’s branches to a point where the thin tip of that branch makes contact with the boardwalk, and onto a 6″ x 6″ post of the boardwalk.

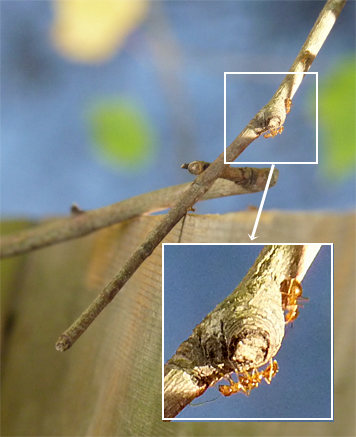

After climbing up the post and onto the railing, the ants hiked 90 or so feet around half of the octagonal shaped landing and down the rail to a point where a very slender willow twig brushes up against another 6″ x 6″ post of the boardwalk.

Here, they climbed onto the twig and made their way down along the branch to the trunk, continuing on to the source of all this effort. It’s here, just a few feet above the ground, that I lost sight of the ants (with binoculars) as they climbed down the trunk.

Was there a wound on one of the trees down there in the tangle of trees and shrubs that the ants had tapped into? Were there aphids or psyllids active on the nearby mimosas that were still producing honeydew? Either seems possible.

The ants continued this industry for at least a week. I don’t know why they stopped. Perhaps the sap stopped flowing, or the aphids or psyllids succumbed to the cold. But, I’m sure the members of this colony are, right now, off somewhere else following another trail to another source of sweet goodness.

I’ll be looking for our little honey ants around the sapsucker holes that I’m sure to find later this winter.

amazing photos to go along with the story!!

Thanks Meredith.

Thank you, Ranger Greg. I was a witness – there was definitely a vigorous 2-lane ant highway going for awhile. Fascinating!

Thank you, Wendy.

I found some of our little friends yesterday (12/1) on the Fatsia which is currently in bloom on the Dinosaur Trail.