During June, the list of dragonflies (odes) seen by me at the Museum grew to 31 species. Two new species of dragonfly were seen on the same day (6/17). One of those odes was alive, the other had expired.

The living ode was a Swift Setwing (Dythemis velox), a species that’s common enough in our area but not so common as to be seen on every outing in every location. I usually run into them at a woodland pond or next to slow moving water at a river. They’re typically perched out in the open on a prominent bare branch or similar object next to or over the water with wings held down and forward and abdomen often pointed upward.

Of four setwings that occur in North America, only one is found here in North Carolina and the Swift Setwing is that one.

The other new species was found on the Dinosaur Trail, partially eaten. I wasn’t sure what it was at first since it was missing much of its body.

The head, thorax and abdominal appendages are often important in determining a dragonfly’s identity. All that remained of this unfortunate odonate was a portion of the thorax with a few legs and rear wings still attached. The abdomen, sans appendages, was intact.

The abdominal appendages would have been a great help in IDing this dragonfly. In males, abdominal appendages act as claspers to grip the female behind the head during the transfer of sperm and, in some species, while the female oviposits or lays eggs. The shape of the appendages are specific. A male dragonfly’s appendages can only grasp a female of the same species, they simply won’t fit onto a female of a different species.

The identification process would be more difficult than I had guessed (glad I took a photo, but I should have kept the specimen itself). The pattern on the abdomen was distinctive enough, but there are two small darners in our area (pygmy darners) which have very similar markings on their abdomens, Harelquin Darner (Gomphaeschna furcillata) and Taper-tailed Darner (Gomphaeschna antilope).

If I had the head, thorax, and especially the abdominal appendages it would be easier, but I didn’t have those parts so I was going to have to rely on some other characteristic of these two dragonflies to separate them. One reference mentioned that the Taper-tailed Darner has fewer veins in its wings than does the Harlequin Darner, but what does that mean. Would I have to count all the veins in the wings? Not if I could help it!

Fortunately I have several references, and one “Dragonflies Through Binoculars,” mentions that the Harlequin Darner has two bridge cross-veins on its wings while the Taper-tailed Darner has only one.

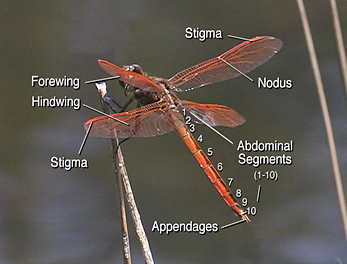

What’s a bridge cross-vein? Well, about halfway out on the forward edge of the wings of dragonflies there is what is called the nodus (see photo above). Here, there is a relatively thick vein that travels back on the wing through a couple of cells to a rather oddly shaped cell in the wing (most of the cells are somewhat square or rectangular) which sort of connects the surrounding cells at a central place in the wing.

Here, see for yourself:

Based on the absence of the second bridge cross-vein, I’ve checked off Taper-tailed Darner on my official list of odonata documented here at the Museum.

If you’d like to see an image of the wings of the other darner, Harlequin Darner, click on this link to G. & J. Strickland’s wonderful scan of this species. Once there, you can download the original scan which allows you to zoom in for a close up view of the wings (click on the icon at top of image labeled “Download Original File”). You can also get a close view of this dragon’s appendages.

Assuming that you clicked on the link, how many bridge cross-veins did you see in the wings of the Harlequin Darner? Two, right? The presence of that additional vein eliminates Harlequin Darner.

So, how did this dragonfly end up partially eaten and discarded on the path on the Dinosaur Trail? I don’t know for sure, but it could have been another much larger dragonfly, or even a wasp or hornet who is responsible for the demise and consumption of the little darner. We’ll never know for sure though, but it has the look of being eaten by an insect and not, for example, a bird.

There are more species out there that I’m sure that I’ve missed, and a few that I’ve seen that I just couldn’t identify, so the list of odes here at the Museum will eventually grow from the current 31 species.

Of course, you don’t have to identify everything that you see, or put a name on every dragonfy that cruises by. You can simply stand on the boardwalk in Explore the Wild and enjoy watching all the differently colored, shaped, and sized odes zipping by you as you gaze out across the water and enjoy them for their beauty, agility, and diverse behaviors.

Happy oding (Happy dragonfly watching).