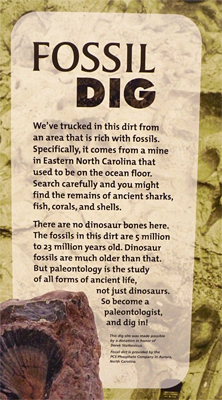

If, before entering, you happen to read the signage at the Fossil Dig Site on the Dinosaur Trail, you will discover that the material through which you are about to search for fossils is of the coastal plain and not of the Piedmont. The gray, coarse material in the Dig Site was shipped in from a phosphate mine near Aurora, NC and at one time was on the bottom of the ocean when that part of North Carolina was under water.

If you stop and read the sign at the Fossil Dig Site you will also learn that the material in the Dig Site was deposited on the ocean floor during a period of about 5 to 23 million years ago.

What you will not learn from the sign is that the boulders that surround the site, and that are also found along the pathways and exhibits of the Dinosaur Trail, Explore the Wild, and Catch the Wind, are some 200 million years older than the “dirt” in the Dig Site.

That same ancient rock also makes up the rock “walls” that you pass as you descend the boardwalk into Explore the Wild and which forms a natural barrier around half of the Black Bear Enclosure.

Durham, NC lies in what is called a Triassic basin, the Deep River basin to be exact (the Durham Sub-basin of the Deep River basin to be even more exact). When the continental plates which comprise what is now North America and Africa began to move apart some 220 million years ago (during the Triassic Period – two geologic periods before the dinosaurs depicted on the Dino Trail were trotting about the landscape), rifts or cracks began to appear in the earth’s crust with at least one of the rifts widening enough to become an ocean basin, the Atlantic Ocean basin. The other rifts, and there are many along the eastern seaboard, became lesser basins filling with silt, clay and other sediment brought in by rivers and streams from the higher ground of the surrounding areas. Over time, those sediments became layered, sedimentary rock.

The boulders, rocks, and rock walls that you see at the Museum are igneous rock, which means that they cooled and solidified from molten rock. This molten rock, or magma, intruded between layers of the already existing sedimentary rock in the Durham Sub-basin, which makes this rock intrusive igneous rock. And, because it flowed between the layers of the sedimentary rock, the formation is referred to as an intrusive sill.

When molten rock lying below the surface (magma) cools deep within the earth the magma cools slowly allowing crystals more time to form and so are larger and visible to the naked eye. You can see the grain in the rock.

When molten rock flowing above ground (lava) cools and solidifies on the surface it cools at a relatively quick rate. Crystals have less time to form and so are small and often not visible to the naked eye. You can not see the grain in the resulting rock without magnification (not to confuse you more, but rock that cools above ground is called extrusive igneous rock since the molten rock, or lava, extruded from the ground).

The rock here at the Museum cooled very close to the surface (but still below the surface) and so is intermediate between the two. The grains in the rock are visible, but are small. It is fine grained rock and, this particular rock, is referred to as basaltic diabase.

The Wetlands and floor of the bear enclosure make up the bottom of a quarry that was in operation in the early 1930’s and which supplied the local area with crushed rock to surface its roads. If you stand at the Black Bear Overlook and look at the rock face to your left (where the A/V kiosk and scent displays are) you can see vertical lines in the rock.

The vertical lines in the rock are the remnants of holes drilled down into the rock by quarry workers in order to insert explosives for blasting the rock away from the face of the cliff.

Throughout the outdoor areas of the Museum you’ll notice much of the rock is stained various shades of green, brown, orange, and black, among other hues. These colors are on the surface only. The true color of the rock is gray, about 50% gray or darker.

If you’re now thoroughly confused, don’t worry, for some of us it’s not an easy thing to learn, this geology. It was quite a while before I actually understood (I think I understand) what all this rock lying about the Museum grounds is, why it’s here, and why it’s different from rock in other parts of North Carolina.

If you want to learn more about the rock formation here at the Museum, and many other geologically important and interesting areas of the Carolinas, I suggest that you read Exploring the Geology of the Carolinas, it certainly helped me to understand some of what I look at everyday as I make the rounds on the paths and trails at the Museum.

One of the authors of Exploring the Geology of the Carolinas, Mary-Russell Roberson, used to work here at the Museum. I didn’t know her but, quite by coincidence, I’m sitting in the office she occupied as I write this.

Geology is something that can be studied and enjoyed in all seasons; the rocks don’t migrate, loose their leaves, or hibernate. Stop by the Museum and have a look for yourself, I promise you that the rocks will be here, and be easy to locate, when you arrive.

What stains the rocks different colors if they are gray under the surface?

Good question.

I don’t know the cause of all the staining on the rock surface, but many of the rocks and boulders that are along the paths and exhibits are the color that they are due the soil from which they were removed. The most obviously stained rock is the red-orange colored rock. This rock gets its color from the clay that makes up much of the Triassic basin’s soil in our area.

Other darker rocks get their color from various other minerals in the soil and water run-off from above. Some of the gray-green, as well as the splotched orange and reddish colors, come from lichen growth on the rock.

I’ve even noticed some rock that has a deep purple color to it. This could be lichen or mineral caused staining, I can’t say for sure. Anyone else out there willing to give possible causes of the staining of this or other rock here at the Museum, jump in.